This fall, The Chart, an online art journal based in Maine, published the following interview between Hilary Irons and Anna Hepler and Jon Calame. Hilary and Jon were at Hewnoaks together in 2017, and Hilary and Anna were at Hewnoaks together in 2018. Here they’re discussing a new collaborative publication by Anna and Jon issued by Orbis Editions in November, 2018, available here.

To see the original post and other articles visit thechart.me. Reposted with permission.

Floating Through Silence and Noise: Anna Hepler & Jon Calame’s “Trespasses”

by Hilary Irons

Forthcoming from Orbis Editions, Anna Hepler and Jon Calame’s new book, Trespasses, is a non-representationally cinematic tour of an interior landscape experienced through blinkered senses. The limited-edition artists’ book presents a series of photographs by Hepler, directly followed by an essay by Calame. First we are immersed in a silent, graceful, visual float through Hepler’s photographs of contemplative but unrelentingly non-linear constructed spaces. After theses images, which are punctuated by severe black pages — functioning as starts and stops similar to the black leader in a filmstrip — the reader/viewer encounters Calame’s essay, “Laacoön’s Spear.” Instantly the velvety space dissolves into sharp, incorporeal sound. Thinking about the sequence and form this book-object takes, as well as the content and narrative possibilities it offers, I presented Hepler and Calame — a married pair of abstract thinkers currently based in Western Massachusetts — with some questions about their work.

Hilary Irons: The collaborative book you have been working on, Trespasses, follows a set of rules that seem to organize time and sensory experience very specifically for the reader. I am thinking of the content of the imagery and language, but also the form the book takes: first we encounter a set of photographs by Anna Hepler (representing interior spaces with arched passageways and no logical sense of up-and-down), which embody the silence of the cell (the cell as a primary unit, or a still image in a cinematic sequence, but also a cell for the faithful in the time of Fra Angelico). The photos lead the viewer (reader) into a place of sensitized awareness, in which silence is felt and recognized, and time becomes slow and abstract. This progression of images is followed by the text (an essay examining the sibilant sound of sss and the resulting influence of that sound on our understanding of the content of, for example, recited prayer), and the viewer/reader’s sensitized state is immediately subjected to the imagined aural, and the perceived silence contained within the photos is replaced by loud and sustained hissing. Time, as well, not only seems to speed up, but also becomes crystalized in the specificity of references: Jon’s childhood, Tyndale’s translation of the Bible into English, the invasion of Troy via wooden horse statue, etc. How did you two, as collaborators, imagine the form the book would take, and the way that form might influence the content of each section, leading to a combined reading of a single artwork?

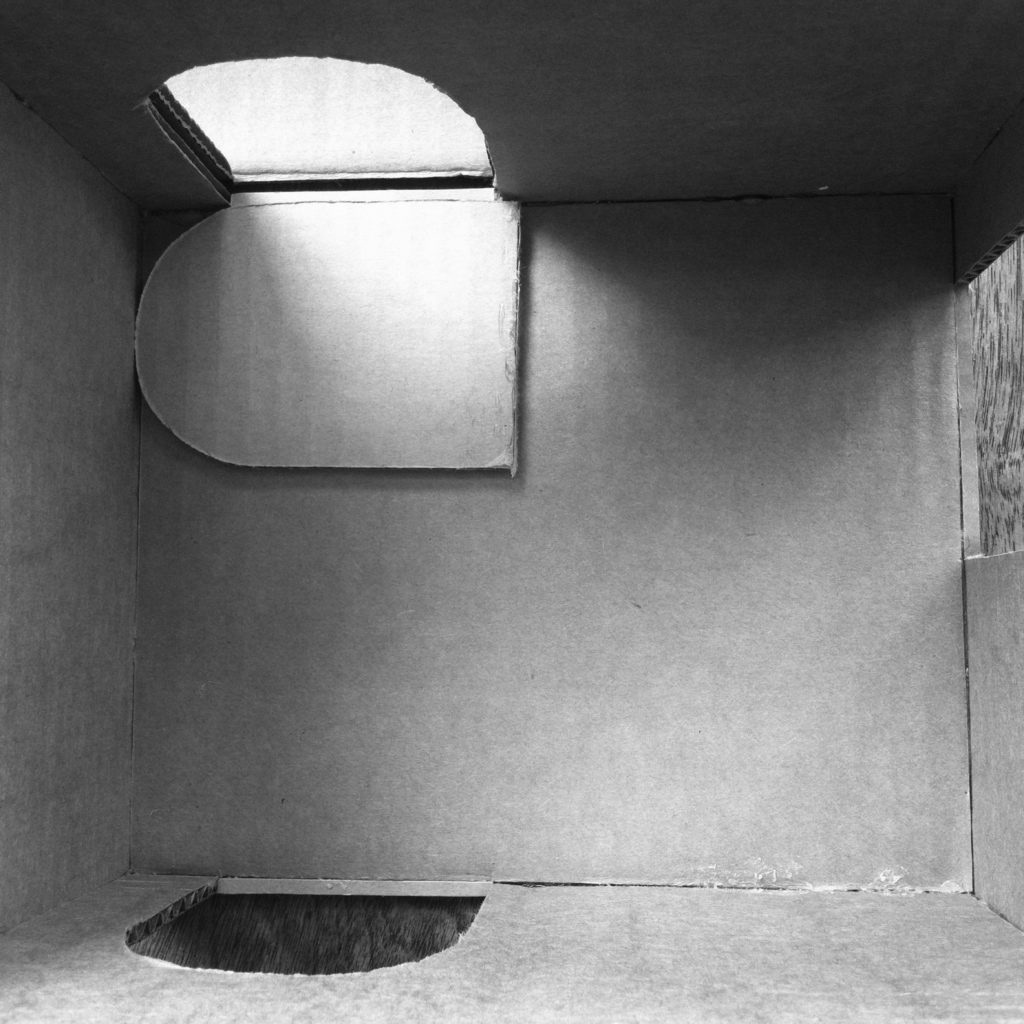

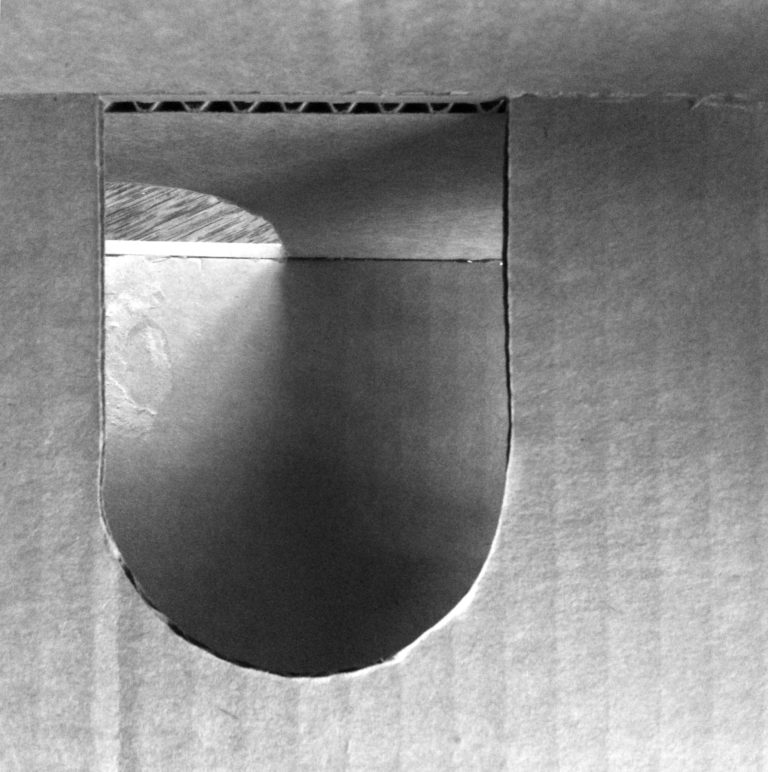

Anna Hepler: Jon and I were just trying to suss out which came first, or what influenced what, and we both agree that it was a very organic parallel process, with some cross pollination. Initially, I planned to put selected images of finished sculptures alongside an essay by Jon who would, in language, attempt a similar shape-shifting, 2D to 3D transformation. Much of my work makes some kind of loop from 2D to 3D and back again resulting in sculptures that read as flat graphics, or drawings that appear three-dimensional. From this original intention came Jon’s memory of the snakes — language into pure sound! I knew that Jon was leaning in this direction for his essay when I left for a residency at Hewnoaks, so the snakes impacted the architecture — the arched doorways — that repeat themselves through my quiet diorama spaces. Specifically, imagining the quiet interiors of abandoned churches. So there is a connection, albeit organic, but we worked very independently not intentionally interweaving our parts. This is reflected again in the book structure where images are separate from words. I love how Jon’s essay supplies sound for the silent diorama spaces.

Jon Calame: It is interesting to imagine the accidental sounds of the Lord’s Prayer falling into, or emerging from, Anna’s little cardboard rooms. I like to think this would be a bit compatible, since Anna’s spaces in this case are a bit complicated, and confusing, and disorienting, which is a similar emotional shape to the ones I was trying to describe.

That said, I was not responding to those spaces (or the images of them) when I wrote the essay. Anna and I were working approximately in a simultaneous and uncoordinated fashion on this project, which for both of us reached its first full draft from scratch over the space of about a month. For two weeks of that period, Anna was working in beatific seclusion at Hewnoaks while I was with our kids in Maine. I suppose during that period Anna knew more about the content of what I was trying to do — since I had discussed the theme with her — than I knew of her particulars. Perhaps she can say what, if any, direct influence my topic had on her choices.

I can say that as long as I have been looking at Anna’s work and thinking about it, which is about 17 years now, I have been wondering if there is any way to respond to it usefully with writing. (Probably we should wonder a lot more than we do about this issue in relation to any artist’s work, regardless of style or medium.) On the whole, I never did think there was. Anna agrees, I believe, though once in a while someone said something on paper that she liked. On the whole, though, Anna does not start with words or themes or concepts or notions, does not incorporate them directly into her work in any way (it has no literary, textual, or political substance whatsoever, for example), and does not fiddle with it after it is made using any of those tools, though she is very articulate about her work in other ways. Titles are a terrible chore for her, for instance.

One wonders, in a case like this, what is the point of talking or writing about it? Isn’t that why an artist like Anna chose to be a visual artist? Isn’t it a pity that the art industry always wants to pin a patronizing note on to the raincoat of a piece of visual art as if it were some lost, drooling kindergarten student who is lactose intolerant? Yes, I think the answer is yes.

But then when this chance to work together on a single publication came along, we rethought the problem. For me, the thing worth worrying about in much of Anna’s work — at any scale, in any medium — is the phase shift between dimensions or material behaviors. That is, I like the way Anna’s work often implies volume when it is flat, or flatness as a volume, or flexibility when it is rigid, etc. Sometimes you just don’t quite know what you are looking at, or what it is capable of doing. In this gap of uncertainty or vertigo, which is generally brief and not ever meant to be nauseating or obscure, lots of nice things can happen. The brain is searching for templates and forms. It is rifling through its Rolodex. However fleeting, these are, or can be, extremely fertile microseconds and they are the ones which most often make me feel interested in Anna’s work and her process, since I believe this pattern is on her part only partially intentional.

I decided, in light of these general impressions of Anna’s work accumulated over time, to reject any kind of direct description. That would be attempting to clarify, and clarity is certainly not the goal, nor condensing. Rather, I tried to find an analogy in the realm of language. The one that came to mind was the “trespasses” problem in the Lord’s Prayer, a childhood impression, and one that always seems oddly “real” to me because you can decide to hear it any time you want, anywhere that controversial version of the prayer is spoken in English. What happens then is genuinely (to my ear) shocking, but is generally unrecognized and unmentioned, which seems to make it more real, for cynical reasons. (Having scoured the internet a bit, I dare to suggest here that I may be the first person ever to write about this deeply obvious, wildly recurrent, superficial, and internationally ritualized voiceless alveolar sibilant anomaly.* (This cannot really be true, naturally, but I am still waiting for a published colleague.) The congregation’s stubborn insistence on hearing only the preferred meanings of the words overrides what is the much more present, visceral fact of a sudden, spatially ambiguous feral hissing which would, in other less philosophically eclipsed contexts like a library reading room, be ideally suited to arrest a person’s attention.

So that is interesting for political reasons. For mechanical reasons, we might say, it is perhaps tangentially similar to some of Anna’s work because of course a word is sort of popping out of its prescribed shell of meaning and going rogue as a renegade sound. Of course I chose this example (one of zillions which can be identified, with little effort, in the bowels of any language) because it is sinister, dramatic, and happens to occur in large, ornate public spaces, which surely adds to the melodrama. When a printed word seems to wriggle out of its proper posture, as the “long S” did both typographically and aurally at the time when this version of the Lord’s Prayer was written, it brings excitement because it means that jailbreaks are still possible. Like those guys who swam past the sharks to leave Alcatraz.

In this case, it is snakes, not persons, but same difference. The danger and uncertainty of it are interesting to me. What else could happen, if this happens? How tightly bolted down is the whole enterprise? Where are the seals and gaskets between parts loose, or leaking? To date, raising these kinds of highly un-answerable questions is the closest I have come to a reply in words to Anna’s work. To the extent — which is quite large, I think — that my essay is an unsuccessful piece of writing, it is a beginning of a satisfactory reverberation of those parts which are most elusive and interesting.

HI: It sounds like the composition of the final object of the book was approached with a kind of loose communicative experimentation, in terms of how your individual sections ultimately intersected in book form. I love what Anna says about the shape-shifting that occurs with the juxtaposition of the words and images, and the way Anna’s photos are first interspersed with black pages and then give way to the noise of Jon’s text. The way this controls the reading of the text, after first having sunk into the imagery, reminds me of the beginning of Chris Marker’s 1983 documentary Sans Soleil: ”The first image he told me about was of three children on a road in Iceland, in 1965. He said that for him it was the image of happiness and also that he had tried several times to link it to other images, but it never worked. He wrote me: one day I’ll have to put it all alone at the beginning of a film with a long piece of black leader; if they don’t see happiness in the picture, at least they’ll see the black.”

The idea of architecture as content leading to an eventual architectural form for the book is so compelling. To me, the photos feel very much like portraits of lived spaces, impossible though they may be, rather than art historical fantasies such as (for example) those which can be found in the work of Piranesi, who I feel is the closest equivalent. Could you, Anna, tell me how you encounter the architecture you experience in daily life, or on travels, and what influence this might have had on your photos?

AH: I do not see my cardboard spaces in the Trespasses photographs as references to specific places or buildings. Architecture is indeed important in my life and I spend an inordinate amount of time thinking about spaces, both for their functionality (home and studio) and for their uncanny personalities and energy (as in the case of making monumental installations within buildings). The closest reference to these cardboard dioramas is the North Church in Eastport, Maine where, in its abandoned stillness, I constructed a boat hull from repurposed cardboard, suspended along the nave (this was in 2016). Abandoned spaces that once were home to a community, and filled by their hopes, fears, and wishes, have intensely vivid energy, like a haunting. Because Jon’s text referenced his experiences in church, I did find myself thinking about memory and abandoned sanctuary spaces that exist in so many small rural towns.

What interests me specifically about dioramas are the illusions that are so easily created. If I use a blunt and recognizable material like corrugated cardboard, can I still create a space that invites the human imagination to enter? Can I then capture the honesty and bluntness of material at the same time as creating an imaginary space, such that the brain flicks back and forth along that knife’s edge? Perhaps it is the efficiency of thinking huge on a miniature scale, and confounding expectations, landing instead somewhere between abstraction and illusion, that makes a project like this interesting. Once photographed, and rendered on a gray scale, the boundaries are further blurred.

HI: Jon, one of the things that kept surfacing for me as I read ”Laacoön’s Spear” was the idea of Pentecost, when the individual languages of humans were subsumed beneath a new noise, which was spiritually rather than intellectually generated. “And suddenly there came a sound from heaven as of a rushing mighty wind, and it filled all the house where they were sitting / And there appeared unto them cloven tongues like as of fire, and it sat upon each of them / And they were all filled with the Holy Ghost, and began to speak with other tongues, as the Spirit gave them utterance,” Acts 2:2-4.

In your essay, the sound of S has the power to transform actual content as well as abstract recognition of meaning: “Underneath any famous words, poets may discover faint melodies, satirists circus trumpets, and great thinkers a raw squawk, but I, whatever I may be, could hear from that morning forward, out of the bowels of the L’sP, a denatured and disjointed hissing.” This passage follows a sequence in which a basket of snakes, overturned, fills a small church with the hissing sound that is echoed in the word “trespasses.” What, if any, other words do you encounter (frequently or infrequently, in daily life or in some kind of ritual) that seem to have a similar power to transform meaning, through the force of their literal sound in your native language?

JC: I had not thought about the Pentecost, since I do not know much about it. I have heard about speaking in tongues, which I guess is somehow distinct from speaking WITH tongues, which all of us can do. So it is not so terribly impressive. “In tongues” surely does sound…snaky. Also, I remember that the Pentecostalists also handle snakes in addition to, or simultaneously with, speaking in this forgotten language. I read that this aspect is on the wane and was mainly done in rural areas of America by a small number of sects.

Why snakes, when their Biblical associations are so negative? Perhaps just to prove that the holy spirit is at work and genuinely protective. Andrus Kivirähk’s The Man Who Spoke Snakish suggests that humans and snakes have a longstanding, but currently forgotten, kinship, which adds complexity to the Pentecostal example.

Regarding your question about other words that slipped a disk and seem to retreat into sound and away from meaning…I do not have many. The Tyndalian trespass is the prize pumpkin for me, especially with all the “ess” sounds that pile up in that one phrase. Still, there are a few further reflections to make. First, your inquiry made me realize that this very same sound is quite ubiquitous and powerful even when severed from meaningful words. The clichés of “pssst!” for an oncoming secret or “shhh!” in a library suggest that this sound has a naturally arresting quality. It cuts through things without necessarily interrupting them or taking them over. It sort of sidewinds around. I note that historically a bad performance in front of an audience was susceptible to hissing as a strong signal of disapproval; luckily now performers do not have to worry about this threat very much. In any case, the sibilant sound is threatening, it is a copper wire of sound to carry anger or raw energy, one might say.

This body of associations makes the problem of hissing in the English recitation of Tyndale’s Lord’s Prayer more strange and subversive, in that it introduces a dangerous sound and implication right in the middle of what is supposed to be a very solemn, deferential moment of lop-sided negotiation with God. But let’s go back to parallel examples.

There are tongue-twisters which are popular mainly among pre-adolescent children. Perhaps they are among the last to really hear the language they speak, in the sense that they take pleasure in minor moments of alienation, such as: She sells seashells by the seashore. Here, the desire to become entangled in esses is explicit. The phrase arranges itself so that there is a fairly balanced tug-of-war between the tongue’s ability to form the words and the ear’s ability to gather up their meaningful, or abstract, content. When the tongue stumbles, the exercise falls to one side of the ridge (meaning blurred by sound), and when it is nimble things fall to the other side (sound supporting meaning, and thereby sort of self-destructing in the way successful language tends to do.). Others in this popular genre are

What a shame such a shapely sash should such shabby stitches show. (So old fashioned. Do we know the words “sash” or “stitch” anymore?)

Six sick slick slim sycamore saplings.

and

Sally is a sheet slitter, she slits sheets.

Thrilling is the destructive action of the Sally Sibilant. They are vicious and unpredictable like blades that hack and slice at host words. We listen, with pleasure it seems, as our brain fumbles for control over the sound-concept pairings; here we can laugh at what is not funny in a stutterer. We enjoy these artificial skirmishes that end in an unlikely and fleeting victory.

Another case of partly disembodied language is the punchline of a shaggy dog story. As you may recall, this kind of joke is about breaking all the rules of joke-telling, so that the narrative goes on too long, switches direction, sets up and then defies comic expectations, and always ends with a punchline which is usually disappointing or a meaningless play on words. One nice specimen involves a King Short Cake who dies, and no one agrees about what to do with the body, and finally a young woman intervenes by saying “Squaw bury Short Cake.” I bring this up because it is an art form that leads us away from normal ways of hearing and receiving language, exhausting and frustrating us, so that in the end we hear things in a less sure, guarded way, and thereby language has a holiday while we momentarily subvert the authority of its meanings, its comprehensive colonization of sound.

I dislike doing it because it is always so pretentious, but it is only fair to cite Barthes again here with his most excellent “Myth Today” essay (1957). He notes that myth is a parasitic form of speech that captures meanings in any format (words, images, notions, phrases, etc.) and then sort of gores them, or empties them out, and injects new concepts, so that the original language becomes the “raw material” for mythical speech. There is an image of a vessel re-purposed, or a cuckoo bird putting its eggs into another’s nest, to be hatched and raised by others. He describes this as a purposeful process of alienation (of constituent forms and associations) which is done to appear “at once intellective and imaginary, arbitrary and natural.” The concept injected into the husk is described by Barthes as conveying knowledge that is “confused, made of yielding, shapeless associations”; this is the feeling I got from the trespass problem in the Lord’s Prayer, though I do not feel sure about whether that one is intentional in the way Barthes studied mythical speech or not. It is, certainly, creepy.

This creepy quality to all language, the way danger and slippage (even violence and aggression) are just below its paper-thin surfaces, seems worth examining. We skate so confidently on the surface, even as the Spring approaches. Every so often, though never around this pond, you hear stories.

Anna Hepler and Jon Calame’s Trespasses (2018, Orbis Editions) was created in part with grant support from the Kindling Fund, a grant administered by SPACE Gallery as part of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts Regional Regranting Program. Trespasses will go on sale on November 10, 2018.

This interview is part of an ongoing collaboration between The Chart and Orbis Editions.

* Wikipedia informs us that “the voiceless alveolar sibilant is the sound in English words such as sea and pass, and is represented in the International Phonetic Alphabet with ⟨s⟩. It has a characteristic high-pitched, highly perceptible hissing sound. For this reason, it is often used to get someone’s attention, using a call often written as sssst! or psssst!.”